Scottish History

of Moore Family

King makers

Some believe that the Muir Clan can trace its origin right back to the starting point of Scotland as a nation. For years it was thought the Scottish Gaels originated from the Dal Riata tribe in Antrim, in Northern Ireland. At around 500 AD Fergus Mor mac Eirc was forced out of his Antrim home and invaded Argyll where he established a new Dal Riata by kicking out the Picts who were already living there.

This was the start of a chain of events which culminated with the Gaels taking over the Pictish nation and creating a unified kingdom of Alba in the ninth century. Eventually Alba evolved into the Scotland we know and love today. It’s thought that for many centuries the Muirs subscribed to this theory, believing their name originated from Mor. Indeed, a seventeenth century book written by Sir William Mure states that the idea they originated from the ancient Irish tribe of O’More was generally accepted within the family at that time. However, in the late twentieth century archeologists began to doubt the evidence. Now, there are strong grounds for concluding that the Gaels did not invade Scotland at that time. Nevertheless, the Muir clan, often known as Mure, More and Moore, played a major role in the formation of the UK’s Royal families, north and south of the Border.

The turning point which saw them rise from relative obscurity to king-makers began with the Battle of Largs and the brave exploits of Gilchrist Muir. King Hakon of Norway, worried about another Scottish attempt to wrest Argyll and the isles from his control decided on a pre-emptive strike. In July 1263 he left the port of Bergen with 200 ships and by the time he reached the western isles of Scotland his forces had been swelled further. Hakon attacked the mainland with initial success before the Scots began negotiating with him. This was a delaying tactic to enable them to mobilise their forces. During the talks a major storm erupted just off Largs. This forced the Norwegians to attempt to shelter on dry land. The combination of terrible weather and difficult terrain left them wide open to attack and they were unable to re-organise themselves into a fighting force. Consequently the Norsemen suffered a heavy defeat. The Scots were led into battle by Gilchrist Muir and chased the invaders into the sea amid much slaughter. A grateful King Alexander III knighted Muir and gave him the lands of Rowallan near Kilmarnock. He built a tower there and married Isobel the daughter of Sir Walter Cumyn, a powerful landowner nearby with whom he’d previously fallen out. When Cumyn died Sir Gilchrist inherited Sir Walter’s land not only in and around Rowallan but also in Roxburghshire in the Borders. Sir Gilchrist died in 1280, at the age of 80. He had two daughters, Elizabeth and Anicia. The latter married Richard Boyle of Kelburn, anscestor of the Earls of Glasgow, who still own the Kelburn estate near Largs. Sir Gilchrist’s son, Archibald, died in the Battle of Berwick in 1297. Archibald’s grandson, Adam, had two sons and a daughter, also Elizabeth, who was described as being of great beauty and rare virtue. In 1336 Elizabeth Muir married Robert Stewart, the grandson of Robert the Bruce and nephew of King David II of Scotland. He was born in 1316 and was a grandson of Robert the Bruce. His mother, Marjorie, was the Bruce’s daughter. His father was Walter the sixth High Steward of Scotland. Robert took his father’s position as his surname and therefore became the first of the line of Stewart or Stuart kings, who in 1603 also became kings of England. King David was on the throne of Scotland at the time of the wedding but he became an absent monarch. He had invaded England in 1346 but was captured at the Battle of Neville’s Cross, remaining a prisoner at the English court until the Treaty of Berwick in 1357. He was returned to Scotland on payment of a large ransom. In his absence Robert Stewart became the Governor of a Scotland on the brink of civil war. With the king away rival nobles were jockeying for position and armed confrontations were commonplace. The Black Death was rampaging through the population reducing it by more than a quarter. Despite these great pressures Robert quietly and shrewdly built up his power base. David was released in 1357 and when he died without children in 1371 Robert succeeded him. Elizabeth had died in 1355 and so never became queen. She had initially become his mistress. Their marriage was criticised as uncanonical, so in 1349 following a Papal Dispensation they remarried. Their children, uniquely, played a substantial role in the formation of two British Royal families, the House of Stuart and the Hanoverians who followed them. Their direct male heirs ruled Scotland until James V died in 1542. James V’s daughter, Mary, Queen of Scots, then took the reins. Her son, James VI of Scotland then became James I of England. Their descendants ruled both countries until 1714 when Queen Anne died. At that point the Hanoverians from Germany took over and today they still rule the United Kingdom. Elizabeth Mure had several daughters. One of them, Jean Stewart, married Sir John Lyon. Their children became the Earls of Strathmore and Kinghorne. Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon is a direct descendant of the fourteenth Earl. In 1923 she married Albert, the Duke of York, the second son of King George V and Queen Mary. As Duchess of York she became known as the “Smiling Duchess” because of her consistent public expression. In 1936, her husband unexpectedly became King when her brother-in-law, Edward VIII, abdicated in order to marry his mistress, the American divorcée Wallis Simpson. Her daughter Elizabeth II is the reigning Hanoverian monarch.

King Robert II and Elizabeth Muir had several sons. Their first was John Stewart who went on to become King Robert III in 1390 after his father died. One of his brothers became the notorious Wolf of Badenoch. This was Alexander Stewart, the fourth, and youngest, son of Robert and Elizabeth. Alexander is infamously remembered for his sacking of Elgin and its cathedral. His nickname was earned due to his outrageous cruelty. In May 1390, after a feud with Bishop Alexander Bur of Moray, Alexander Stewart, by now the Earl of Buchan, burned the Royal Burgh of Forres and the Church of St Lawrence. The following month he burned a large part of Elgin including the cathedral, a monastery, churches and a hospital. Buchan disliked Bishop Bur because the churchman had helped the Earl’s wife, Euphemia the Countess of Ross, successfully file for divorce. The couple had no children but the Earl fathered several with his mistress, Mairead Inghean Eachann, including Alexander Stewart who became the Earl of Mar. As a consequence of the divorce Buchan lost a great deal of land which had previously belonged to his wife and now reverted back to her. Buchan died in 1405 and is buried in Dunkeld Cathedral. His armour-covered tomb is one of the few Scottish royal monuments to have survived from the Middle Ages.

There were other strands of the Muir Clan dotted around Scotland in the thirteenth century and a number of them including Gilchrist Muir were of high enough stature to be signatories on the Ragman’s Roll. This was a record of the acts of fealty and homage which King Edward I of England forced Scotland’s nobility and gentry to sign in 1296. Edward was known as The Hammer of the Scots because of his attempts to impose his rule on the land north of the border. Initially, Edward had planned to annex Scotland through marriage. His intention was for his son and heir Edward to marry Margaret the Maid of Norway. She was the daughter of King Eirik II of Norway and Margaret, daughter of King Alexander III of Scotland. The princess was born in 1283 and was sometimes known as Margaret of Scotland and was considered to have been Queen of Scots from 1286 until she died in 1290 with no successor. There were fears that without a clear-cut heir to the Scottish throne a power vacuum would develop and the country would descend into tribal war. In order to prevent this Edward was invited by the nobility and other power brokers of the time to rule on who would be the next king. In return he insisted on the signatures to the Ragman Roll. The Muirs who added their names to it were The Mores of Levenaches’ Adam de More of Ayrshire, Reginald de More of Ayrshire, Gilchrist Muir of Ayrshire, Reynauld Mor of Cragg, Lanarkshire and Symon de la Moore of Thankerton. The list illustrates the variation in the spelling of the surname.

Troubled times

A number of Muirs joined the Covenanters. These were Scots who would not accept that King Charles I was head of the church. They signed a covenant which stated that only Jesus Christ could hold that position.

King Charles inherited the throne in 1625. His father James VI of Scotland became James I of England in March 1603. Scotland’s religion was Presbyterianism, a harsh strict form of Protestantism. King James believed that his rule had a higher authority than the church’s. Despite that he failed in his attempts to force the Scots to embrace his Episcopalian doctrine, which allowed the monarch to appoint bishops to the church. King Charles, who was born in Fife, decided to finish his father’s job. In 1637 he ordered that the Book of Common Prayer should be read in St Giles Cathedral, Edinburgh. The congregation was furious. Many believed it was closer to Catholicism than Protestantism. Seven months later, in February 1638, Scotland’s National Covenant was published. This document, prepared with the full support of the nobility and land-owning class, proclaimed Scotland’s opposition to the king’s new prayer book. It was put on public view in Edinburgh and immediately attracted 60,000 signatures. Copies were taken throughout the country and many more signed up. In 1642 the First English Civil War erupted, between Charles and the forces loyal to his former Parliament, which he had tried to dismiss. The Covenanters allied themselves with the Parliamentarians, known as the Roundheads, who were led by Oliver Cromwell. By May 1646 The Royalists were defeated and Charles surrendered to the Scots. While imprisoned he convinced the Covenanters to switch their allegiance to him in return for a promise to make England a Presbyterian state. Soon after, the Covenanters invaded England in the hope of restoring Charles to the throne. This was the start of the Second English Civil War. But they were no match for Cromwell’s battle-hardened New Model Army and were heavily defeated after a series of battles. When the dust settled Charles was executed by public beheading in January 1649 and Cromwell governed the country. In 1660 the Monarchy was restored and King Charles II was welcomed back to England from exile on the Continent. A year later Banffshire-born James Sharp was appointed Archbishop of St Andrews and immediately began a drive to bring episcopacy to Scotland coupled with a brutal repression of Presbyterianism. Some Covenanters were also signatories of the Apologetical Declaration which declared war on all established political officials, soldiers, judges, conformist ministers, and informers. This document, however, provoked vicious reprisals by the authorities and the period became known as the Killing Times. During 1684-85, at least 78 Covenanters were executed without trial for refusing to retract their allegiance to the declaration, while others were executed after a show trial. Among them was James Muir, who was hanged for his beliefs on February 22, 1684 in Edinburgh.

Family History Mini Book

We hope you enjoyed reading this excerpt from this mini book on the Scottish history of the Muir family.

You can buy the full book for onlyIrish History

of Moore Family

Knights of the Red Branch

Three main sources can be traced for the presence of the proud name of Moore in the Emerald Isle – a name that resonates throughout the island’s long and turbulent story.

There are those Moores who first came to Ireland as adventurers in the wake of the late twelfth century Cambro-Norman invasion and the subsequent consolidation of the power of the English Crown.

These Moores, known by the native Irish as ‘de Mora’ and who settled mainly in the ancient province of Munster, derive their name from a term meaning ‘strong mountain’.

The present day Viscounts of Drogheda trace a descent from Moores who came to hold substantial estates in Mellifont, in Co. Louth.

There was an influx in later centuries of Moores from Scotland, although the more common form of their name was Muir, or More, and were considered septs of the Scottish clans Campbell and Leslie, respectively.

But both the ‘English’ and ‘Scottish’ Moores can be considered relative newcomers to the island when compared with the ancient pedigree of those Moores who were originally known in Gaelic-Irish as Ó Mordha and, later, O’Moore or O’More.

The progenitor, or ‘name father’ of the Ó Mordhas was a chieftain known as Mordha, with the name thought to denote ‘stately’ or ‘noble’.

Mordha, in turn, was in direct line of descent from one of the greatest figures in the illustrious roll call of Irish warriors – none other than Conal Cearnach, better known as Conal of the Victories.

He is a character steeped in the rich and heady brew that is Celtic myth and legend.

His father was Amairgen, famed for slaying a three-headed creature that dwelt in the underworld, while his mother was Findchaem, the daughter of a druid known as Cathbad.

But it was as a first century AD chieftain of the Craobh Ruadh, or Red Branch Knights, that Conal Cearnach achieved his own fame.

Charged with the defence of the province of Ulster, the Red Branch Knights were an aristocratic military elite whose seat was at Emain Macha, an ancient hill fort whose ruins can be seen to this day about two miles west of Armagh.

Also the seat of the kings of Ulster, Emain Macha, or Fort Navan, boasted three great halls.

One was where the king and the Red Branch Knights feasted and slept, while another contained the province’s treasury and a grisly display of the heads of slain enemies.

Finally there was the hall known as the speckled house, where the warriors’ weapons were stored, while the Bron-Bherg, or Warrior’s Sorrow, served as their hospital.

While Conal Cearnach was chief of the Red Branch Knights, their greatest champion was his foster brother and blood cousin Cúchulainn, known to posterity as The Hound of Ulster.

It was at Emain Macha that Cúchulainn met and fell in love with the beautiful Emer, described as ‘the best maiden in Ireland’, because she possessed what were known as the six precious gifts.

These were the gift of beauty, the gift of voice, the gift of sweet speech, the gift of needlework, the gift of wisdom, and the gift of chastity.

Chaste she would remain, however, refusing Cúchulainn’s hand in marriage, until he had proven himself a mighty warrior.

Accordingly, he set off for the Land of Shadows, better known as the Scottish Inner Hebridean island of Skye, to receive training in the martial arts under the expert tutelage of the warrior princess known as Scathach.

His intense training lasted for a year and a day, by which time he had become an adept in skills whose true nature we can now only guess at.

They included the apple feat, the thunder feat, the feats of the javelin and the rope, the body feat, the feat of the sword-edge and the sloped-shield, the pole throw, the noble chariot fighter’s crouch, the feat of the cat, the leap over the poison stake, the breath feat, the spurt of speed, the stunning shot, and the stroke of precision.

Scathach also presented Cúchulainn with the Gae Bolg, or ‘belly spear’, a ferocious weapon that, once it was driven inside the victim’s body, released thirty deadly barbs that ripped the stomach apart, and a magical sword, known as Caladin.

Cúchulainn was transformed into a virtual killing machine under Scathach’s tutelage.

When the ‘battle frenzy’ took hold of him, it was said that he turned around in his skin so that his feet and knees were to the rear and his calves and buttocks to the front.

To complete this ferocious transformation, it was said that ‘one eye receded into his head, the other stood out huge and red on his cheek; a man’s head could go into his mouth; his hair bristled like hawthorn, with a drop of blood on each single hair; and from the ridge of his crown there arose a thick column of dark blood like the mast of a great ship.’

Cúchulainn was eventually slain in battle through an act of treachery, and it was Conal Cearnach who avenged him by killing Mosgora Mac Da Thó, king of the province of Leinster.

Not content with merely slaying his enemy, Conal then took the dead king’s brain and, mixing it with lime, made the magical slingshot known as a ‘brain ball.’

With St. Fintan as their patron saint, Conal’s descendants became the leading sept of what were known as ‘The Seven Septs of Leix’, or Laois.

One of their strongholds sat atop the forbidding Rock of Dunamase, just under five miles from present day Portlaoise, while a Cistercian abbey was founded in 1183 at what is now the township of Abbeyleix by Conor O’More, or O’Moore.

The political and military landscape of Ireland became transformed following the Cambro-Norman invasion of 1169 and the subsequent influx of English settlers and adventurers.

English dominion over the island was ratified through the Treaty of Windsor of 1175, under the terms of which Irish chieftains were only allowed to rule their territory in the role of a vassal of the king.

There were the territories of the privileged and powerful Norman barons and their retainers, the territory of the disaffected Gaelic-Irish such as the O’Moores, and the Pale – comprised of Dublin and a substantial area of its environs ruled over by an English elite.

The island groaned under a weight of oppression that was directed in the main against native Irish clans, and one indication of the harsh treatment meted out to them can be found in a desperate plea sent to Pope John XII by Roderick O’Carroll of Ely, Donald O’Neil of Ulster, and a number of other Irish chieftains in 1318.

They stated: ‘As it very constantly happens, whenever an Englishman, by perfidy or craft, kills an Irishman, however noble, or however innocent, be he clergy or layman, there is no penalty or correction enforced against the person who may be guilty of such wicked murder.

‘But rather the more eminent the person killed and the higher rank which he holds among his own people, so much more is the murderer honoured and rewarded by the English, and not merely by the people at large, but also by the religious and bishops of the English race.’

The province of Ulster proved particularly stubborn in its resistance to the encroachment of the power of the English Crown, and the Ó Mordhas, or O’Mores, or O’Moores, were for centuries at the forefront of this resistance.

Defenders of liberty

An organisation founded in the U.S.A. in 1836 known as The Ancient Order of Hibernians, and that now functions as a Catholic Irish-American fraternal body, traces its roots back to a Rory Oge O’Moore.

In the words of the Order it was O’Moore who ‘organised and founded Hibernianism in the year 1565 in the county of Kildare, in the province of Leinster, and gave his followers the name of The Defenders.’

These ‘Defenders’ were responsible in 1599 for one of the greatest defeats ever inflicted on an English Royalist army in Ireland – at the evocatively named Pass of the Plumes, about six miles from what is now Abbeyleix.

It was in the Pass of the Plumes that a highly disciplined band of O’Moore guerrilla fighters and their allies killed no less than 500 troops under the command of the Earl of Essex.

The scene of the battle takes its name from the hundreds of plumed English helmets that lay scattered across the blood-soaked killing ground.

In the same year as the battle of the Pass of the Plumes Owney Macrory O’Moore added insult to English injury by imprisoning the powerful Duke of Ormonde.

O’Moore expressed what he thought of the English presence on his territories by releasing the duke with the humiliating addition of a millstone tied around his neck.

Matters came to an explosive head in 1641 when landowners rebelled against the English Crown’s policy of settling, or ‘planting’ loyal Protestants on Irish land.

This policy had started during the reign from 1491 to 1547 of Henry VIII, whose Reformation effectively outlawed the established Roman Catholic faith throughout his dominions.

In the insurrection that erupted in 1641, at least 2,000 Protestant settlers were massacred, while thousands more were stripped of their belongings and driven from their lands to seek refuge where they could.

England had its own distractions with the Civil War that culminated in the execution of Charles I in 1649, and from 1641 to 1649 Ireland was ruled by a rebel group known as the Irish Catholic Confederation, or the Confederation of Kilkenny.

One of the main driving forces of this confederation was Colonel Rory O’Moore.

Terrible as the atrocities against the Protestant settlers had been, subsequent accounts became greatly exaggerated, serving to fuel a burning desire on the part of Protestants for revenge against the rebels.

The English Civil War intervened to prevent immediate action, but following the execution of Charles I and the consolidation of the power of England’s Oliver Cromwell, the time was ripe was revenge.

Cromwell descended on Ireland at the head of a 20,000-strong army that landed at Ringford, near Dublin, in August of 1649.

He had three main aims: to quash all forms of rebellion, to ‘remove’ all Catholic landowners who had taken part in the rebellion, and to convert the native Irish to the Protestant faith.

An early warning of the terrors that were in store for the native Irish came when the northeastern town of Drogheda was stormed and taken in September and between 2,000 and 4,000 of its inhabitants killed.

The defenders of Drogheda’s St. Peter’s Church, who had refused to surrender, were burned to death as they huddled for refuge in the steeple and the church was deliberately torched.

Cromwell soon held the benighted land in a grip of iron, allowing him to implement what amounted to a policy of ethnic cleansing.

His troopers were given free rein to hunt down and kill priests, while rebel estates were confiscated, including those of the O’Moores whose stronghold atop the Rock of Dunamase was razed to the ground.

An edict was issued stating that any native Irish found east of the River Shannon after May 1, 1654, faced either summary execution or transportation to the West Indies.

One source that speaks of Colonel Rory O’Moore’s role in the abortive rebellion states how: ‘Then a private gentleman, with no resources beyond his intellect and courage, this Rory, when Ireland was weakened by defeat and confiscations… conceived the vast design of rescuing the country from England.

‘History contains no stricter instance of the influence of an individual mind.’

Many native Irish such as the O’Moores were forced to seek refuge on foreign shores, and among their number was Murtagh O’Moore, who settled in France and whose descendants to this day form part of the French nobility as Lords of Valmont.

Another branch of the family who settled in Spain returned to Ireland in the mid-eighteenth century and built Moore Hall, in the province of Connacht.

It was a son of this family, John Moore, who played a brief and tragic role in the history of Ireland when it again exploded in a fury of discontent during the Rising of 1798 - an ultimately abortive attempt to restore Irish freedom and independence.

The Rising was in essence sparked off by a fusion of sectarian and agrarian unrest and a desire for political reform that had been shaped by the French revolutionary slogan of ‘liberty, equality, and fraternity.’

A movement had come into existence that embraced middle-class intellectuals and the oppressed peasantry, and if this loosely bound movement could be said to have a leader, it was Wolfe Tone, a Protestant from Kildare and leading light of a radical republican movement known as the United Irishmen.

Despite attempts by the British government to concede a degree of agrarian and political reform, it was a case of far too little and much too late, and by 1795 the United Irishmen, through Wolfe Tone, were receiving help from France – Britain’s enemy.

A French invasion fleet was despatched to Ireland in December of 1796, but it was scattered by storms off Bantry Bay.

Two years later, in the summer of 1798, rebellion broke out on the island, centred mainly in Co. Wexford, while a small French invasion force commanded by General Humbert landed at Killala.

The rebels achieved victory over the forces of the British Crown and militia known as yeomanry at the battle of Oulart Hill, followed by another victory at the battle of Three Rocks, but the peasant army was no match for the 20,000 troops or so that descended on Wexford.

Defeat followed at the battle of Vinegar Hill on 21 June, followed by another decisive defeat at Kilcumney Hill five days later.

On landing at Killala General Humbert had declared that Connacht was henceforth a republic and appointed John Moore as its president.

He was destined to pay dearly for this – being captured after the rebellion collapsed and dying in prison in Waterford.

Another John Moore also played a role in the 1798 Rising.

This was the British Army general Sir John Moore, who was born in Glasgow in 1761 and who commanded part of the British forces in Ireland at the time of the rebellion.

The general, who was killed in 1809 at Corunna during the Spanish Peninsular campaigns, is credited with having curbed some of the worst excesses against the defeated rebels.

Family History Mini Book

We hope you enjoyed reading this excerpt from this mini book on the Irish history of the Muir family.

You can buy the full book for only79 Clan Muir

Tartan Products

The Crests

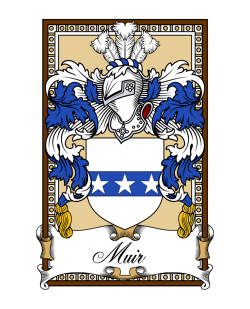

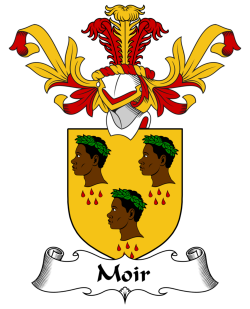

of Clan Muir