Clan Kerr

LATE BUT IN EARNEST

Clan Kerr originate from the Scottish Borders, and were one of the infamous Border Reiver clans.

Originally descending from two brothers, Ralph and John Ker, clan Kerr were prominent Crown vassals by the 15th century and gained a number of titles, including the Earldom of Lothian - a title upgraded to Marquess of Lothian at the beginning of the 17th century.

Interestingly, the Kerr clan were traditionally associated with left-handedness, and some of their clan dwellings - such as Ferniehirst Castle near Jedburgh - were designed with this in mind.

The Kerr clan motto is "Sero sed serio" (Late but in earnest) and the clan crest is a sun.

Scottish History

of Car Family

Feuds and vendettas

Despite a bitter and bloody feud that raged for more than 300 years between rival branches, the great Borders family of the Kerrs also brought their considerable martial prowess to bear in support of successive Scottish monarchs and, in later centuries, Britain’s mighty empire.

It was in recognition of these contributions that the family became the recipients of a plethora of glittering honours, including earldoms and a dukedom.

Numerous derivations have been advanced for the name ‘Kerr’. One is that it comes from the Gaelic ‘caerr’, meaning ‘left’, and that this relates to a Kerr family trait of being predominantly left-handed.

This, some claim, is where the Scottish expressions ‘Kerr-fisted’ and ‘cori-fisted’, to describe someone who is left-handed, originate.

Another possible derivation is from the Gaelic ‘ciar’, meaning ‘dusky’, and is said to relate to those Kerrs found on the west coast of Scotland and the island of Arran.

One other colourful derivation, but wholy fabulous, is one that can be traced back to Biblical times, with ‘Kerr’ in Hebrew being ‘Kir’.

In the Brythonic language of the ancient Britons the word for ‘fort’ was ‘caer’, and may be another possible derivation of ‘Kerr’.

The likeliest derivation, however, is from the Norse word ‘kjerr’, taken variously to mean copsewood or brushwood, or a marsh dweller.

In the decades following the Norman Conquest of England in 1066, many of the Normans had settled in both England and Scotland.

The Normans, of course, stemmed from the original Vikings, or Norsemen, who settled in France and gave the name of Normandy to the vast province they controlled.

It is probable that one of these Norman families were known by their Norse name of ‘Kjerr’, and that this was later anglicised as ‘Kerr’.

The name, spelled with a single ‘r’, is first recorded in the Scottish Borders in 1190, and concerns a transaction involving one Johannes Ker, an Anglo-Norman who had settled near the present-day town of Peebles.

Confusingly, over the subsequent centuries, different branches of the Kerrs opted to spell their name with either a single ‘r’ or two. The name also appears as ‘Carr’ and ‘Carre’.

Two brothers, Ralph and John, are recognised as the founders of the two rival Kerr families that for centuries held sway in the Borders. The main branch was the Kerrs of Ferniehirst, who claimed descent from Ralph, and the Kerrs of Cessford, who claimed descent from John.

Although of the same bloodline, the Kerrs of Ferniehirst and the Kerrs of Cessford were engaged in a virtual civil war with each other until Anne Kerr of Cessford married William Kerr of Ferniehirst in 1631.

It is from this marriage that the Earls and Marquisses of Lothian trace their descent, while the son of Sir William Kerr of Ferniehirst was created the 1st Lord Roxburgh, in 1637.

Following the Act of Union between Scotland and England in 1707, the 5th Earl of Roxburgh was created Duke of Roxburgh.

This title passed in 1805, following a failure in the line with the death of the 3rd Duke of Roxburgh, to Sir James Innes of that Ilk, who took the name of Innes-Ker.

The Marquess of Lothian is today recognised as Chief of the Clan Kerr, while the Duke of Roxburgh is Chief of Clan Innes.

The original source of the bad blood between the Kerrs of Cessford and the Kerrs of Ferniehirst is lost in the mists of time, and when they were not engaged in civil war with one another they were embroiled in deadly disputes with other Border families such as the Armstrongs, Maxwells, Homes, Swintons, Davidsons, Turnbulls, Grahams, Scotts, Douglases, and Elliots.

A bitter feud, for example, had existed between the Kerrs of Cessford and the Scotts ever since Sir Andrew Kerr of Cessford, who had been one of the few Scots nobles to survive the Battle of Flodden in 1513, had been killed by one of Scott’s retainers at a battle near Melrose in 1526.

The Church attempted to broker a resolution to the feud in 1530, by arranging a bond, or agreement, under which Sir Walter Scott of Branxholm, laird of Buccleuch, was obliged to undertake what were known as the four head pilgrimages of Scotland in reparation for the slaying of Kerr of Cessford.

This required that he said a mass for the soul of Cessford at the four locations of Melrose Abbey, Paisley Abbey, Scone Abbey, and the Church of St. Mary, in Dundee.

Sir Walter’s pilgrimage of penance failed to heal the rift between the Kerrs and the Scotts, however. A Scott laird of Buccleuch was killed by a Cessford in the streets of Edinburgh in 1552, and despite another attempt made in 1564 to reconcile the two families, they were still at loggerheads until at least as late as 1596.

In the same year, a 20-strong armed band of Turnbulls and Davidsons presented themselves before the Jedburgh residence of Sir Andrew Kerr of Ferniehirst, and after what a contemporary account describes as various ‘brags, insolent behaviour and menacings’ of Sir Andrew and his servants, they cold-bloodedly killed Sir Andrew’s brother, Thomas, and one of his servants.

Although eleven men eventually came to trial, only one Turnbull paid the price when he was beheaded at the Cross of Edinburgh.

In the bloody atmosphere of mafia-style vendettas that then prevailed in the Borders, Turnbull’s execution only resulted in further tit-for-tat killings, while the constant feuding made the Borders one of the most wild and unruly parts of the kingdom.

A Privy Council report of 1608 graphically described how the ‘wild incests, adulteries, convocation of the lieges, shooting and wearing of hackbuts, pistols, lances, daily bloodshed, oppression, and disobedience in civil matters, neither are nor has been punished.’

Wardens of the March

A constant thorn in the flesh of both the English and Scottish authorities was the cross-border raiding and pillaging carried out by well-mounted and heavily armed men, the contingent from the Scottish side of the border known and feared as ‘moss troopers.’

In an attempt to bring order to what was known as the wild ‘debateable land’ on both sides of the border, Alexander II of Scotland had in 1237 signed the Treaty of York, which for the first time established the Scottish border with England as a line running from the Solway to the Tweed.

On either side of the border there were three ‘marches’ or areas of administration, the West, East, and Middle Marches, and a warden governed these.

Complaints from either side of the border were dealt with on Truce Days, when the wardens of the different marches would act as arbitrators. There was also a law known as the Hot Trod, that granted anyone who had their livestock stolen the right to pursue the thieves and recover their property.

The post of March Warden was a powerful and lucrative one, with rival families vying for the position. The marches became virtually a law unto themselves.

In the Scottish borderlands, the Homes and Swintons dominated the East March, while the Armstrongs, Maxwells, Johnstones, and Grahams were the rulers of the West March.

The Kerrs, along with the Douglases and Elliots, held sway in the Middle March, and in 1502 a Kerr of Ferniehirst was appointed Warden of the Middle March.

There is no doubt the family abused this influential position, not only at the expense of other Border families, but at the expense of the rival Kerrs of Cessford.

The roles were reversed eleven years later when a Kerr of Cessford was appointed to the post and exacted vengeance against the Kerrs of Ferniehirst for the abuses they had suffered under their tenure as masters of the Middle March.

This proved to be a pattern that would be repeated in succeeding years as loyalty to the Crown determined which of the Kerrs should hold the post.

The rift between the Ferniehirsts and the Cessfords deepened following the death of James IV at the Battle of Flodden in 1513, and the remarriage of his widow Margaret Tudor to the Douglas Earl of Angus.

In the complex and rapidly shifting loyalties of the time, the Kerrs of Ferniehirst supported the cause of the young James V, while the Cessfords supported Margaret.

In the near anarchy following the death of James IV in 1542, Sir John Kerr of Ferniehirst’s castle was taken and occupied by an English force. All the Kerr women and servants were brutally raped by the English garrison.

When the castle was recaptured seven years later, the garrison were tortured before being killed. The incident is the subject of Walter Laidlaw’s poem, The Reprisal.

The Kerrs of Cessford and the Kerrs of Ferniehurst took opposing sides in the cause of the ill-fated Mary, Queen of Scots, with Sir Thomas Kerr of Ferniehirst fighting for her doomed cause at the Battle of Langside, while Sir Walter Kerr of Cessford fought on the side of the band of nobles supporting the cause of the infant James VI.

Mary had earlier escaped from Lochleven Castle, in which she had been imprisoned after being forced to sign her abdication, by a body known as the Confederate Lords.

Kerr of Ferniehirst was among a group of nine earls, nine bishops, 18 lairds, and others who signed a bond declaring their support for her, and both sides met at Langside, near Glasgow, on May 13, 1568.

Mary’s forces, under the command of the Earl of Argyll, had been en route to the mighty bastion of Dumbarton Castle, atop its near inaccessible eminence on Dumbarton Rock, on the Clyde, when it was intercepted by a numerically inferior but tactically superior force led by her half-brother, the Earl of Moray.

Cannon fire had been exchanged between both sides before a force of Argyll’s infantry tried to force a passage through to the village of Langside, but they were fired on by a disciplined body of musketeers and forced to retreat as Moray launched a cavalry charge on their confused ranks.

The battle proved disastrous for Mary and signalled the death knell of her cause, with more than 100 of her supporters killed or captured and Mary forced to flee into what she then naively thought would be the protection of England’s Queen Elizabeth.

Kerr of Ferniehirst was also forced to flee, and it is testimony to his loyal adherence to Mary that, following his death in 1584, even an English chronicler was moved to write that he had been ‘a stout and able warrior, ready for any great attempts and undertakings, and of an immoveable fidelity’.

During the Queen’s unhappy time in Scotland, another Kerr, Andrew, played a key role in one of the most brutal incidents in Scotland’s murderous history.

The victim was Mary’s musician and secretary David Rizzio, who had first come to the Scottish court in 1561 in the train of the Piedmontese ambassador.

Born in Turin, the talented Italian quickly won the favour of the Queen, brightening up the dourness of her court with his musical performances and compositions.

As the Queen’s secretary, however, ‘Signor Davie’ performed a more serious role. Gifted in a number of foreign languages, the Italian helped to draft the secret correspondence between the Queen and what was known as the Catholic League, particularly the Spanish royal court.

This made him highly suspect and dangerous in the eyes of Scotland’s Protestant nobles, who feared a concerted conspiracy to overturn the nation’s Reformed religion.

Rizzio also flagrantly flouted his favoured position at court, while dark rumours were spread that it was he who was actually the father of the pregnant Queen’s child, and not her husband, Lord Darnley, whom she had married in 1565.

The Protestant lords played on the dissolute and gullible Darnley’s vicious pride to such an extent that he entered into a bond, or agreement, with them, to solve the problem of the upstart Italian once and for all by arranging for his murder.

The most prominent nobles involved in the drama that was played out on the night of March 9, 1566, were the Lords Ruthven, Murray, Morton, and Lindsay, although they also had the active support of retainers and other Scottish magnates, including Andrew Kerr.

On the night that was to prove the hapless Rizzio’s last one on earth, Lord Darnley brought a number of the heavily armed men into his own chamber at the Palace of Holyrood and then led them up a secret stair into his wife, the Queen’s, apartments.

It was an innocent scene that greeted the murderous band as they entered one of the Queen’s small chambers. Heavily pregnant, she reclined on a low couch, surrounded by a number of loyal retainers and favourites, including Rizzio.

A fierce argument ensued over this unpardonable breach of her privacy and words quickly led to violent deeds as the armed men attempted to wrest the cowering Italian from the chamber.

Clinging to the Queen’s gown for protection, he was pulled away, ripping the rich fabric in the process. As he was dragged from the room, pleading and screaming for mercy, Andrew Kerr brutally held a pistol to the Queen’s breast to prevent her from going to the doomed Italian’s aid.

His pleas for mercy in vain, Rizzio was stabbed and slashed repeatedly with daggers, before his lifeless body was unceremoniously thrown down a flight of stairs into the porter’s lodge, where the porter lost no time in stripping the fine clothing from his bloodstained corpse.

Many of those involved in Rizzio’s murder, including Andrew Kerr, escaped subsequent punishment, but Lord Darnley himself was murdered in mysterious circumstances just under a year later.

Family History Mini Book

We hope you enjoyed reading this excerpt from this mini book on the Scottish history of the Kerr family.

You can buy the full book for onlyEnglish History

of Car Family

Ancient roots

A name with a number of possible derivations, ‘Carr’ has been present throughout the British Isles and Ireland from the earliest times.

One derivation is from the Old Norse ‘kjarr’, indicating ‘swamp’, ‘marshland’, ‘brushwood’ or ‘low-lying meadow’ and the name may have arisen as a locational name indicating someone who lived in such areas.

Its Scottish variants are ‘Car’, ‘Ker’ and ‘Kerr’, while the Scottish-Gaelic form is ‘Cearr.’

Forms of the name found in Ireland include ‘O’Cara’, indicating ‘descendant of Cara’, with the name in this case meaning ‘spear.’

Yet another theory concerning the origin of the name is that it stems from the Old Welsh ‘cwarr’, meaning ‘giant.’

Despite being found in numerous forms throughout Britain and Ireland, it is in Lancashire, in the north of England that the name is particularly identified.

This is through a family who were granted lands there by William of Normandy for their assistance at the 1066 battle of Hastings.

Bearers of the name today who can trace a family ancestry rooted in Lancashire may well be of original Norman roots, while bearers who can trace a Celtic ancestry rooted in Scotland, Ireland or Wales may be of early British or Anglo-Saxon stock.

This means that flowing through the veins of the Carrs of today is a rich and heady brew of several bloodlines.

The Anglo-Saxons were those Germanic tribes who invaded and settled in the south and east of the island of Britain from about the early fifth century.

They were composed of the Jutes, from the area of the Jutland Peninsula in modern Denmark, the Saxons from Lower Saxony, in modern Germany and the Angles from the Angeln area of Germany.

It was the Angles who gave the name ‘Engla land’, or ‘Aengla land’ – better known as ‘England.’

They held sway in what became England from approximately 550 AD to 1066, with the main kingdoms those of Sussex, Wessex, Northumbria, Mercia, Kent, East Anglia and Essex.

Whoever controlled the most powerful of these kingdoms was tacitly recognised as overall ‘king’ – one of the most noted being Alfred the Great, King of Wessex from 871 to 899.

It was during his reign that the famous Anglo-Saxon Chronicle was compiled – an invaluable source of Anglo-Saxon history – while Alfred was designated in early documents as Rex Anglorum Saxonum, King of the English Saxons.

Other important Anglo-Saxon works include the epic Beowulf and the seventh century Caedmon’s Hymn.

Through the Anglo-Saxons, the language known as Old English developed, later transforming from the eleventh century into Middle English.

The Anglo-Saxons had usurped the power of the indigenous Britons – some of whom would have been forebears of some of the name of Carr today – and who referred to them as ‘Saeson’ or ‘Saxones.’

It is from this that the Scottish Gaelic term for ‘English people’ of ‘Sasannach’ derives, the Irish Gaelic ‘Sasanach’ and the Welsh ‘Saeson.’

We learn from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle how the religion of the early Anglo-Saxons was one that pre-dated the establishment of Christianity in the British Isles.

Known as a form of Germanic paganism, with roots in Old Norse religion, it shared much in common with the Druidic ‘nature-worshipping’ religion of the indigenous Britons.

It was in the closing years of the sixth century that Christianity began to take hold in Britain, while by approximately 690 AD it had become the ‘established’ religion of Anglo-Saxon England.

The first serious shock to Anglo-Saxon control of England came in 789 AD in the form of sinister black-sailed Viking ships that appeared over the horizon off the island monastery of Lindisfarne, in the northeast of the country.

Lindisfarne was sacked in an orgy of violence and plunder, setting the scene for what would be many more terrifying raids on the coastline of not only England, but also Ireland and Scotland.

But the Vikings, or ‘Northmen’, in common with the Anglo-Saxons of earlier times, were raiders who eventually stayed – establishing, for example, what became Jorvik, or York, and the trading port of Dublin, in Ireland.

Through intermarriage, the bloodlines of the Anglo-Saxons became infused with not only that of the indigenous Britons but also that of the Vikings.

But there would be another infusion of the blood of the ‘Northmen’ in the wake of the Norman Conquest of 1066 – a key event in English history that sounded the death knell of Anglo-Saxon supremacy.

By 1066, England had become a nation with several powerful competitors to the throne.

In what were extremely complex family, political and military machinations, the English monarch was Harold II, who had succeeded to the throne following the death of Edward the Confessor.

But his right to the throne was contested by two powerful competitors – his brother-in-law King Harold Hardrada of Norway, in alliance with Tostig, Harold II’s brother, and Duke William II of Normandy.

In what has become known as The Year of Three Battles, Hardrada invaded England and gained victory over the English king on September 20th at the battle of Fulford, in Yorkshire.

Five days later, however, Harold II decisively defeated his brother-in-law and brother at the battle of Stamford Bridge.

But Harold had little time to celebrate his victory, having to immediately march south from Yorkshire to encounter a mighty invasion force, led by Duke William of Normandy that had landed at Hastings, in East Sussex.

Harold’s battle-hardened but exhausted force of Anglo-Saxon soldiers confronted the Normans on October 25th in a battle subsequently depicted on the Bayeux tapestry – a 23ft. long strip of embroidered linen thought to have been commissioned eleven years after the event by the Norman Odo of Bayeux.

It was at the top of Senlac Hill that Harold drew up a strong defensive position, building a shield wall to repel Duke William’s cavalry and infantry.

The Normans suffered heavy losses, but through a combination of the deadly skill of their archers and the ferocious determination of their cavalry they eventually won the day.

Anglo-Saxon morale had collapsed on the battlefield as word spread through the ranks that Harold had been killed – the Bayeux Tapestry depicting this as having happened when the English king was struck by an arrow to the head.

Amidst the carnage of the battlefield, it was difficult to identify Harold – the last of the Anglo-Saxon kings.

Some sources assert William ordered his body to be thrown into the sea, while others state it was secretly buried at Waltham Abbey.

What is known with certainty, however, is that William in celebration of his great victory founded Battle Abbey, near the site of the battle, ordering that the altar be sited on the spot where Harold was believed to have fallen.

William was declared King of England on December 25th, and what followed was the complete subjugation of his Anglo-Saxon subjects.

Those Normans who had fought on his behalf were rewarded with the lands of Anglo-Saxons, many of whom sought exile abroad as mercenaries.

Within an astonishingly short space of time, Norman manners, customs and law were imposed on England – laying the basis for what subsequently became established ‘English’ custom and practice.

Honours and distinction

It was in the aftermath of the Norman Conquest that an originally Norman family who became known as ‘Carr’ were rewarded with lands in Lancashire.

A John del Carr is recorded here in 1332, while much further south in Lincolnshire the Carr Baronetcy of Sieford was created in 1611 for Edward Carr, who served as sheriff of the county.

In the Scottish form of ‘Kerr’, bearers of the name flourished as Clan Kerr, with the two main branches the Kerrs of Cessford and the Kerrs of Ferniehurst.

The Chief of Clan Kerr holds the title of Marquess of Lothian.

One of the most colourful and controversial bearers of the Carr name and one who figures prominently in the historical record following the Union of the Crowns of England and Scotland in 1603, was Robert Carr, 1st Earl of Somerset.

Born in 1587 in Wrington, Somerset, the younger son of Sir Thomas Kerr (Carr) of Ferniehurst, it was as a favourite of James I (James VI of Scotland), that he gained high honours and political influence.

In 1601, serving as a lowly page to George Hume, 1st Earl of Dunbar, he met Sir Thomas Overbury.

They became firm friends, with Overbury later assuming the role of Carr’s mentor, secretary and political adviser.

Carr apparently needed the help of someone like the wily Overbury, with one source describing the younger man as being ‘entirely devoid of all high intellectual qualities, but endowed with good looks, excellent spirits and considerable personal accomplishments.’

In 1606, three years after the Union of the Crowns under James I, the nineteen-year-old Carr broke a leg during a tilting match at which the 40-year-old monarch was present.

James reputedly had an eye for handsome and dashing young men, and is said to have instantly fallen in love with Carr – teaching him Latin while helping to nurse him back to health.

So infatuated was he with Carr that he knighted him, while in 1607 he controversially conferred on him the substantial English manor of Sherborne, which had been forfeited from the estate of the executed Sir Walter Raleigh.

Further honours rapidly accrued to the once lowly page, including being made a Privy Councillor and created Viscount Rochester.

In 1613, Carr married Frances Howard, Lady Essex, whose marriage to Robert Devereux, 3rd Earl of Essex, had been nullified.

This was the same year in which James advanced Carr to the Earldom of Somerset and appointed him Treasurer of Scotland.

In 1615, by which time Carr also held the powerful post of Lord Chamberlain, he was replaced in the king’s affections by the young George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham.

Through the complex political machinations of the time, Carr also turned against his faithful mentor Sir Thomas Overbury.

Accused of being complicit in his murder by poisoning in July of 1615, both Carr and his wife were brought to trial along with four others.

All were found guilty, but only the four others were executed.

Still retaining some influence over James, the lives of Carr and his wife were spared and both were eventually pardoned.

The one-time favourite of James I died in 1645, while his daughter Anne later became the wife of the 1st Duke of Bedford.

Bearers of the Carr name have entered the historical record not only on British shores but also much further afield.

Nicknamed “The Black-Bearded Cossack”, Eugene Asa Carr was a noted Union Army general of the American Civil War of 1861 to 1865.

Born in 1830 in Hamburg, New York and graduating from the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1850, he went on to receive the Medal of Honor – America’s highest award for military valour in the face of enemy action.

This was for his actions at the battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas in March of 1862, when he led the 4th Division of the Army of the Southwest.

His Medal of Honor citation states how he had “directed the deployment of his command and held his ground, under a brisk fire of shot and shell in which he was several times wounded.”

Later commander of the 2nd Division of the Army of Southeast Missouri, which became a division of the Army of Tennessee, he led the attack on Confederate forces at the battle of Port Gibson, during the Vicksburg Campaign.

He died in 1910.

Yet another Medal of Honor recipient was William L. Carr.

Born in 1878 in Peabody, Massachusetts, he had been a private in the United States Marine Corps during the 1898 to 1901 Boxer Rebellion in China – an uprising that opposed foreign imperialism.

It was for his bravery in action in Peking in both July and August of 1900 that he was awarded the medal; later promoted to the rank of corporal, he died in 1921.

From the battlefield to the world of politics, Robert Carr is the Australian politician better known as Bob Carr.

Born in 1947 in Matraville, Sydney, he holds the record at the time of writing for the longest continuous service as Premier of New South Wales.

This was from April of 1995 to August of 2005, while the Labor politician was elected a member of the Australian Senate for the state of New South Wales in 2012, serving in the government as Minister for Foreign Affairs.

In Canadian politics, Shirley Carr was the prominent activist on behalf of trades unions who was the first female president of the Canadian Labour Congress, Canada’s largest labour organisation.

Born in Niagara Falls, Ontario, in 1929, she served from 1969 as general vice-president of the Canadian Labour Congress until her appointment in 1974 as executive vice-president of the congress.

Made an Officer of the Order of Canada in 1980 and a Member of the Order of Ontario in 1995, she served as president of the congress from 1986 to 1992; she died in 2010.

Also in Canadian politics, Adriane Carr is the political activist and academic who in 1983 was a co-founder of the Green Party of British Columbia, North America’s first Green Party.

Born in 1952 in Vancouver, and the holder of a master’s degree in urban geography, in 2001 she became the first Green Party candidate elected to a major Canadian city council.

This was when she stood for the Green Party of Vancouver.

She is married to the environmental campaigner Paul George, one of the founders of the Western Canada Wilderness Committee.

Family History Mini Book

We hope you enjoyed reading this excerpt from this mini book on the English history of the Kerr family.

You can buy the full book for only113 Clan Kerr

Tartan Products

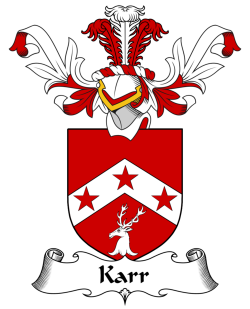

The Crests

of Clan Kerr